tv Book TV CSPAN December 24, 2012 10:00am-11:15am EST

10:00 am

>> it was only as i got into it and i kept discovering more and more things i realized this was not impersonal market forces, this was not technology, this was not globalization. what was happening was american politics and american economics were working against the middle class. people did this. we decided this. if you look at other countries like germany, their middle class is in better shape. they've done better trading against the world, their companies are making money. so a lot of the things we heard that were not impossible, not possible in america are actually happening in germany, and their wages have gone up five times faster that than ours.

10:01 am

there's something wrong inside the american economic and political system, and that's what this book is about. >> host: hedrick smith is the author. thank you for being on booktv. >> from the fourth annual boston book festival, a panel featuring author edward glaeser. it's about an hour, 15. >> good afternoon and thank you very much for coming to this auditorium today. let me introduce myself, i'm bob oakes from morning edition on wbur, boston's npr news station. [applause] thank you. thank you. i'm sure some of you are saying, wow, that's bob oakes? [laughter] i thought he was taller -- [laughter] i thought he was thinner, i thought he had more hair. [laughter] and, you know, the funny thing is that all those things were

10:02 am

true last week. [laughter] let me thank all of you for coming here this afternoon and thank the boston book festival for having us. don't they do a nice job? isn't this a terrific eventsome. >> yes. [applause] >> let's also thank the plymouth rock foundation for sponsoring this particular session and say that without their generosity, it would be hard to put on events like this that add to the cultural life that we all enjoy in this great city. so so thanks to them. [applause] and in a way that's what we're here to talk about this afternoon, the triumph of this city and all the cities, the triumph of the city, that's the title of harvard economics professor ed glaeser's book. it's about what's made cities around the world great, about the challenges that they have had to overcome and still face. we're going to talk about b that in a few minutes in the special

10:03 am

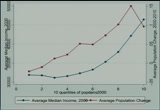

context of this city with our panel, and we'll take questions from you as well later. but, first, to launch us off with a presentation, here's the author, professor ed glaeser. [applause] >> thank you. thank you, bob. and thank you all so much for being here. i'm so enormously flattered that you've decided to take time out of your saturday afternoon to come and talk about, about cities. i'm also particularly grateful to the boston book festival for including this book. i, like i think every single one of you, love books, and i'm just thrilled to be part of this amazing thing that goes on here. well, um, let me start, let me start or with a portrait of america, and i call it a portrait to make it really clear from the very start that i have absolutely no aesthetic sense whatsoever. [laughter] but this is a sort of a portrait. i've taken the 3,000 odd counties in this country, and i've split them into ten. each dot represents roughly 30 counties on the basis of their

10:04 am

density levels. because at their heart, cities are the absence of physical space between people. cities are proximity, density, closeness. the bottom line shows the relationship between density and income. as you can see, there's a steadily increasing relationship there where the densest tenth of america's counties earn on average, on a per capita basis, 50% more than the people living in the least dense half of america's counties. this is a common phenomenon in the united states and throughout the world. the three largest metropolitan areas in this country produce 18% of our nation's gdp, almost a fifth while including only 13% of america's population. the top line shows something that may be somewhat more surprising. it's the relationship between population growth between the years 2000 and 2010. and initial population density. and as you can see, until you get to the very top tenth population growth grows up steadily with density. at the start of the 19th

10:05 am

century, we were leaving our enclaves on the eastern seaboard to spread out, to take advantage of the enormous wealth of the american hinterland. at the start of the 21st century, we're clustering in, we're clack moring to be close to one another. we see in boston the resurgence of a great city. we see it in new york and san francisco and seattle and chicago, all of these places, in the london and paris. we see the try um of the developed world cities. but the success of the city in the developed world is nothing relative to what's happening in the developing world. we've recently reached that halfway point where more than half of humanity now lives in urbanized areas, and it's hard not to think on net that's a good thing because when you compare those countries that are more than 50% urbanized, the more urbanized countries have on average income levels that are five times higher and infant mortality levels that are less than a third. gandhi famously said the growth of a nation depends not on its

10:06 am

cities, but on its villages. but with all due respect to the great man, on this one he was completely and utterly wrong. because, in fact, the future of india is not made in villages which is too often remaining mired in the unending rural poverty that has plagued most of humanity throughout almostal of its -- almost all of it existence. it is mumbai, it is delhi, that are the pathways out of poverty into prosperity. they've the conduits, the channels across civilizations and continents and a place where india's transforming itself from a place that was practically a synonym for poverty and deprivation to a place that is bubbling with opportunity. now, in some sense the success of cities in the modern age is something of a paradox. we live in an age in which distance is dead, in which every sickle one of us -- single one of us could just telecommute in to whatever business employs us,

10:07 am

occupying whatever spot appeals to our biofill ya, and yet in so many ways we choose urban life. we choose the inconveniences, the high cost of living in urban areas. despite the fact that the tech no profits and the cyber sears 20 years ago predicted all this new technology would make cities obsolete. and yet google, which of all the companies in the world should have access to the best long distance working technology, what do they do? they build the google plex so their workers can be right next to one another. silicon valley, right? practically the most famous geographic cluster in the world is also the industry which is the most technologically savvy. why is it that all this new technology far from making face to face contact in the cities that make it obsolete seems to be hypercharging our cities? this relatively rosy view is very unlike the new york of my youth. i was born in manhattan in 1967. i say that warily in the boston public library. [laughter] but i was. and these are two iconic images

10:08 am

from my, from my youth. we could have similar images of new york -- of boston in the 1970s as well. the bottom image is gerald ford denying new york's request for a fiscal bailout. ford didn't literally tell new york to drop dead, but lots of people think he meant it and, indeed, it looked as if new york was very much headed for the trash heap of history. the city had been hemorrhaging manufacturing jobs by the hundreds of thousands in the 1960s and early '70s, the largest industrial cluster in the u.s. in the 1950s was not automobile production in detroit, it was garment production in new york city, and that sector was decimated by globalization and new technology. the city had been caught in a spiral of disorder, rising crime rates, racial conflict just like here in boston, and the fiscal situation had gotten out of control with budgets that were far too high for the city to afford. it looked as if new york was going to go back to the weeds, right? this is an image of jimmy carter

10:09 am

wandering through the wasteland that the south bronx had become, and it really seemed as if the planet of the apes image of the statue of liberty rising from the sand, that that was plausible. that, in fact, these cities were things, you know, whose time had come and gone. in part, the future of the city seemed so dim because their original reasons for being had largely disappeared. if you think about every one of america's older, colder cities, they were all part of solving a transportation problem. they were all nodes on a transportation network. if you go back to 1816, we as americans sat on the edge of an enormously wealthy continent that was virtually inaccessible. in 1816 it cost as much to move goods 30 miles over land as it did to ship them across the entire atlantic ocean. it was so expensive to get goods in. over the course of the 19th century, we've built an amazing network. we built canals like the erie and illinois and michigan

10:10 am

canals, railroads atticaals, and cities grew up. at buffalo, the western terminus of the erie canal. the oldest cities were typically where the river meets the sea, like boston and new york, but every one of america's 20 largest cities was on a major waterway. chicago was a future that was made it the linchpin of a watery arc that went from new york to new orleans. and industries grew up around these transportation hubs. chicago's most famous is, of course, its stockyards, and that's what you're looking at right now. those stockyards were part of the problem of getting the corn that america grows so well then and now, and it would each without utterly beknighted agricultural policies followed by until federal government with subsidizing -- that was a pleatly unnecessary aside -- completely unnecessary aside, i apologize for that. [laughter] originally, it was moved over

10:11 am

vast distances in that quite tasty form of whiskey. we then moved to pigs which are, of course, corn with feet -- [laughter] b we have always preferred salted pork to salted beef, and then once this character, armor, figures out about refrigerated rail cars, you put the blocks of ice on top rather or than below the beef so that cold water drips down, you're able to have a single great stockyard in chicago which is moving that, those corn-fed beef in a cost efficient manner east. now, even though cities form for utterly prosaic reasons, miracles happen when smart people come to being around each other, when they learn from one another. think about athens 2500 years ago, or think about florence 600 years ago in the age of the me dissi where a city built on wool and banking, a city who connected brilliant people and

10:12 am

learned from one another. the basic mathematics of linear perspective, done tell la puts it on the wall of orson kelly who puts anytime a painting in a chapel, that beautiful image of st. peter finding the silver coin in the belly of a fish who puss it a-- passes it along to a less liberal monk. and so it was in chicago where they collaboratively invented the skyscraper in the age of armor and his stockyards. and so it was in detroit when they collaboratively invented a mass-produced car. it's not just about this character, ford, who came to detroit -- a classic inland -- [inaudible] -- working a detroit dry dock, a cutting edge engine company that provided him with the skills he needed. cities then, as now, are fortresses of human capital. it wasn't just about ford, david dunbar, billy durant and charles kirby. collectively, they managed to produce, mass produce

10:13 am

automobiles n. the short run, this was a great thing, right? and, but in the long run it was a disaster. successful cities at the dawn of the 21st century look a lot like successful cities 20 years ago -- 200 years ago; connections to the outside world. how far away is this from the rouge, ford's great factory, walled off from the outside world employing tens of thousands of less educated workers. a wonderful recipe for short-run productivity, a wonderful recipe for paying worker $5 a day. it was factories like this that made detroit quite possibly the most productive place on the planet in the '50s, but these were not a recipe for long-run urban regeneration because they don't need the city, they don't give to the city. they're a world unto themselves. when conditions change, and they always change, you just move the factories to places where it's cheaper. you have nothing left. and so as transportation costs

10:14 am

declined, we moved these factories to lower cost locale, we moved them to the suburbs, we moved them to the right-to-work states and across the country. now, detroit still has not recovered from deindustrialization. in part, detroit had the worst of all possible worlds, it had a single large industry, a few dominant firms. those firms crowded out all local entrepreneurship, and the city has had a significant degree of problems ever since. they have 25% -- they've lost 25% of their population between 2000 and 2010. luckily, not all cities followed this path. we all know, many of us know the story of boston's regeneration transformation from an old industrial textile and other town to a capital of the information age, but it's easy to forget that seattle, 40 years ago two real estate jokers put occupy a sign on the highway asking the last perp to leave the -- the last person to lee the city to turn out the lights because boeing was cutting back

10:15 am

on its jobs. no one could imagine a seattle without boeing. this was before amazon, before costco, before microsoft and starbucks, it's at most the faint whiff of an aroma. seattle came back. it came back because of skills and entrepreneurship just like boston. these are two to have the people who -- two of the people who played an outside role in boston's rebirth of capital ideas. that's the founder of raytheon, adviser to presidents. a man who very much was a statesman who moved the academy into the world of commerce. he was a entrepreneur and, indeed, would go on to become the father of silicon valley on the other side of the country. i couldn't get a non-copyright picture of arthur d. little, so that's arthur d. little hall at mit. [laughter] he started an industry in boston and little was, you know, he was

10:16 am

an academic who then went on to start up the research lab for general motors. now, one variable does better than any other in explaining which older, colder cities came back, and that's skills. the share of the population with a college degree as of 1960 or 1970 does an incredible job of explaining which older, colder cities come back. this is the past ten years from the least skilled to the most, a whopping difference in terms of population growth in the last ten years. if you want to understand why seattle and detroit look very different, you don't heed to look further than 12% of detroit's residents have college degrees while 50% of seattle's do. a college degree goes up by 10%. your wages go up on average by 8%. it's just that valuable to be around skills people. now, the role of skills in explaining why cities come back helps us make sense of the paradox with which i began this talk. the connection between skills

10:17 am

and city growth reflects the fact that a great urban advantage in the world today is to facilitate the flow of knowledge. for what globalization and new technologies have done is they've increased the returns to being smart. they've increased the returns to innovation. because you can sell out on the other side of the planet, you can buy it on the other side of the planet, you're compete anything a global marketplace full of opportunity if you're smart enough to see it. and the more complicated the ideas, the more likely it is to be lost in translation. right? anyone who's ever taught knows the hard thing about teaching is not knowing your script, it's knowing whether anything you're saying is getting through. [laughter] and whether or not, you know, and when you're in the same room, you can take advantage of those wonderful cues that we have evolved over millions of years for communicating comprehension or confusion. in some sense cities are so valuable because they take advantage of humanity's greatest asset which is our ability which we have when we come out of the

10:18 am

womb to just soak up information from our parents, from our peers, from our siblings, even occasionally from our teachers. cities enable us to become smart by being around other smart people. and that's why, that's why google builds the google plex, and that's why boston has come back. that globalization new technologies have made it important to be smart, and this is a city where we can come and be smart by learning from the mistakes and successes of people around us. now, the most important skills that happen in skill, the most important ideas that happen in cities are not, in fact, the skills that are taught in colleges, although those are clearly helpful. they're the skills that are learned afterwards, on the city streets. and there's no skill or talent that's more crucial for urban success than entrepreneurship, the inclinations, the abilities to be an entrepreneur and measures of an -- are very good predicters. fifty years ago an economy

10:19 am

compared new york and pittsburgh and noted new york was more resilient even then. he argued this was a result of the historic concentration in the garment sector which was the mother of entrepreneurship because it was so easy for anybody with a good idea to get started. all you needed was a couple of sewing machines. pittsburgh had u.s. steel, like general motors a fantastically-efficient company in the short run, but not a place that trained entrepreneurs, it trained company men. the middle managers in u.s. steel like the middle managers at general motors would not know how to start an electronic greeting card company if gm went down or us steel went down, but those garment guys, they would. indeed, my book tells the story of the builder of more new skyscrapers than anybody in the 1920s. he got his start in the garment district. he also showed a certain strain towards irrational exuberance. he declared that 1930 would be

10:20 am

the greatest of all building years. he died poor. [laughter] now, of course, not everything about cities is rosy, particularly once you leave the u.s. the same urban proximity that enables people to communicate ideas also enables us to communicate diseases with one another, and if you're close enough to sell someone a newspaper, you're close enough to rob them as well. from the course of, over the course of history, cities have been battling with the demons of density; crime, contagious disease, congestion. this is a map a of death rates in new york from 1800 to today. a boy born in new york city could expect to live seven years less than the national average, today life expectancies are three years longer. we don't understand fully why cities like boston and new york are healthier than denser areas. some people credit walking, more people credit social connection. among younger people, though, it's crystal clear. two big causes for the death, motor vehicle accidents and

10:21 am

suicide, both much rarer. it's a lot safer to get on the t after a few drinks than it is to get behind the wheel of a car. not that i'm recommending anything. [laughter] maybe suicide rates also reflect social connection or the influence of gun culture where there's a strong existence. now, this didn't happen by accident. america's cities and towns only became safe through massive expenditures on water works, right? america's cities and towns were spending as much on water at the start of the 20th century as the federal government was spending on everything except for the post office and the army. unbelievable expense. but there are some urban problems like congestion that require more than just an engineering solution. the problem with building more roads is that it just causes people to drive more. there's something called the fundamental law of traffic congestion that establishes that vehicle miles traveled increase

10:22 am

roughly one for one with highway miles built. if you build it, they will drive, okay? the only way to make sure that our city streets are moved sufficiently is to charge people for it, to actually do what singapore does, second densest country in the world, and yet you can drive around it effortlylessly because they have that electronic road pricing thing that charges you for using these streets. america's cities are running, essentially, a soviet-style urban transit policy. they used to have grocery stores that would give away eggs and butter at far below market prices, the result was you couldn't get the goods. that's what we do with our city streets. they're a valuable commodity, and as a result, they're the urban equivalent of long lines which are traffic jams. there's no path other than actually making people pay for the cost of their actions. now, we already, of course, pay plenty, and one of the enduring challenges of cities is how to make them affordable.

10:23 am

i know of no way to solve this other than building, other than providing more supply for, indeed, there's no repealing the laws of supply and demand. this is actually where jane jacobs got it wrong, because she looked at old buildings and new billion dollarings and notes that old buildings were cheap which led her to conclude that you made sure nobody built any new buildings on top of old buildings. now, that isn't how supply and demand works. you don't neat to look any further than her own district of greenwich village to see the impact of freezing a city in amber. her home district, which was affordable when she and her husband lived there in the 1950s, has turned into a place that is, where townhouses start at $5 million a pop, and only hedge fund managers need apply. that's what happens when you turn off the chain of building new housing. now, one of the reasons why it's so important to furture our cities and -- nurture our cities, and, indeed, allowing more buildings is one way, is

10:24 am

the environment. and i'm going to end by telling a story of a young harvard college graduate, beautiful spring day in 1844 went for a walk in the woods outside of concord, and he did a little fishing, and the fishing was good. and then he came to cook the fish into a chowder. it is boston, after all. [laughter] and the wind came and flicked the flames that he was using to nearby dry grass, and a fire started, and it spread, and it spread. and eventually, it turned into a raging inferno which burn withed down more than 300 acres of prime woodland. in his own day this man was cast away, and it's hard not to see they were right because i can't think of any young man living in boston or cambridge who did as much damage to the environment as this man did. he is, of course, henry david thoreau whose book walden seems to preach a gospel, but his own

10:25 am

life tells a very different story. his own life preaches the moral that we are a destructive species, and if you love nature, stay away from it. [laughter] as, indeed, thoreau would have done the world a wonderful amount of good if he had stayed home. now, there is a modern equivalent of this which is when people, and i need to make it clear i know about this. when i started acquiring small children about seven years ago, only economists talk about acquiring small children. [laughter] i, too, moved to an area not far away from where or thoreau lived, and i started doing almost as much damage. and the reason why people in suburbs tend to do significantly more environmental damage is much longer car drives and much larger housing units. one way of thinking about this is if the great growing economies of india and china see their emission levels rise to the levels of the united states, global carbon levels go up 30 %.

10:26 am

that's a huge difference. and whether or not you believe in global warming or you're just worried about the price of gas at the pump, we all have a lot to gain by china and india building up rather than out. and i think the most important thing for america to do in order to encourage that to happen is get its own urban policies in order, and that means stop treating our cities as if they are the ugly stepchildren of america and recognize them for the intellectual heart lambed, the cultural heartland of this country. and to me that means rethinking policies that act as if the american dream can only mean being a homeowner in the suburbs. it means rethinking policies that pay for highways with general tax revenues, focusing above all on our city schools which are such critical ingredients for urban success and such a critical problem which despite enormously hard work by people like mayor menino, like the city council, like leaders throughout this country are still so far from what they should be.

10:27 am

and, of course, finally, allowing enough building so that every young couple that wants to live in a city can actually afford it. but i don't want to end on something bleak. despite the challenges this world faces, the track record of our species when we work together, when we are powered by our cities is just tremendous. and i have every piece of optimistic belief that cities will continue to power humanity's future and create marvelous things for centuries, if not millennia to come. thank you. [applause] >> ladies and gentlemen, ed glaeser, i think what we just learned in the last few minutes in addition to learning a lot more about how 40 our cities developed is that no one sleeps in ed glaeser's classes at harvard. [laughter] and, by the way, he'll be signing books in the lobby of the auditorium up above once we're done.

10:28 am

let many introduce our panel. in decision to ed, ayaan that pressley, good afternoon. >> good afternoon. hi, everyone. good to see you. [applause] >> and senior adviser to mayor menino, barbara berke. barbara, good afternoon. [applause] and i want you to take us -- let me start this way. i want you to take us a little further back, because in the book you say that boston's rebirth has as much to do with recent politics as what happened in the 1630s. explain. >> so the f we think about -- if we think about where boston, how boston came back, it's hard not to place an outside role for the or education that this city has always invested in. and, indeed, you know, we have the example of bush above, and he's an example of one of the people who brought the academy into entrepreneurship. now, boston's path towards education didn't start with mit,

10:29 am

although mit is an example of the land grant colleges that have a remarkable correlation between land grant colleges and the subsequent success of different metropolitan areas in the country. but if you think about boston's turn towards education, it didn't happen in the 18th or 19th centuries. it happened when the first bostonians almost 400 years ago came here and decided to create the boston latin school and then use state funding to create harvard. these were investments that then set the course for years afterwards. i mean, i often think of it that you really need to just have, you know, a vastly high degree of education to possibly believe that crossing the atlantic, to be able to be with people that think that dancing is a sin is a great idea, right? you really need to be highly educated to think that's a swell idea. [laughter] and if you think back, the roots of our educational investment aren't always so attractive. we thought that, you know, harvard was a great institution, but we were very worried about,

10:30 am

you know, the jesuits leading the kingdom of the antichrist i think was a word that was often used to describe the fears of the jesuit education in the new world. so we were part of this deeply religiously-frack white house world, and our universities and our schools were seen as being a critical investment in that. it worked out for the best, of course. but its roots go back to the religious fractures of the early 17th century. >> so if boston's, if boston as a center of higher education continues to bear fruit for us, continues to reward us, does the mere presence -- ayaan that, let me ask you this question -- does the mere presence of tufts, bcbu and all the guarantee, do you think, that we stay that way in the future? >> there are certainly never any guarantees. i always believe that the best economic development strategy is to attract and train smart

10:31 am

people and then more or less get out of their way. so that's basically what's the best thing we can do. it's still no guarantee, but we face significant challenges which is there's just an incredible river of talent that runs through our schools. it's hard convincing them to stay in boston. >> right. >> yes. >> a couple of years ago, i chaired this boston citizens committee for the future of boston, and i spent a lot of time having conversation with 20-somethings about why they, what they thought was troubling about boston and why they wanted to leave. a lot of them objected to high prices and said, look, i can go to new york and have a better night life. a lot of them were complaining about the t not running after midnight. i hadn't seen the bar side for a very long time. i was not aware that the t stopped at midnight. and part of it, of course, is just how open the city is to entrepreneurship, to new start-ups. and that's certainly that the or mayor with the innovation district has been very focused

10:32 am

on. but i mentioned earlier that having a lot of little establishments is an indicator of both entrepreneurship and subsequent success. suffolk county is terrible on this measure, right? andst not just the issue of a few industries like health care. this is not a county that traditionally has had lot of start-ups. it's been dominated by large scale, often older employers. and i'm thrilled that the mayor is now concentrating on it, but we've got to make sure the river of talent stays here. >> with ayanna wants to weigh in. >> yes. so recently i was at the democratic national convention, and james carville reminded me there that with all the talk about the economy that we don't live in an economy, we live in a society. and i care deeply about the kind of society that we are creating. and i use the word "creating" on purpose. today community does not happen organically. we have to be very intentional and deliberate about that.

10:33 am

and while the city council is currently in the midst of a school reassignment process, i've learned that quality is subjective, the definition of that. while the city council is in the middle of a redistricting process, i've learned that community is subjective and how neighborhood is defined. so i do believe in investing in infrastructure and all those things that would, um, eradicate or mitigate a brain drain. but ultimately i believe that it doesn't matter if we have more affordable housing or better jobs or better schools if people don't want to live here. and that has everything to do with community and the soul of a city. people want to be a part of a city that is diverse and inclusive and welcoming. neighborhood is about social

10:34 am

interaction. and that's really how we build community. and in a city like boston that has 22 distinct neighborhoods, which i'm very proud to represent them as one of four at-large boston city cowns records, we have to be very intentional about how we foster those social interactions. and i think that we would be giving short shrift to these larger sort of macro issues if we didn't speak about what's really at the heart of it. and you want people to want to be a part of a community. and the last thing i would say, at least for now, is that, um, i studied latin when i was in school, and i was recently spending time with a linguist who was remarking that, um, both young people and adults are often referring to where they reside as their hood, that we have all but taken out of the word neighbor and how critical it is that we start to put that

10:35 am

back in in our language and what impact that might have. >> barbara berke. >> well, i was going to build on that point of what neighbors do for the hood, because -- [laughter] community has changed a lot. it used to be when people came to a community, even when immigrants came to a community, they came to a tight, small community, there were faith-based communities, there were schools where everyone in the school was integrated around serving the child and the parent and finding clothing and services. everybody in the community was lifting everyone else up. >> right. >> and we went through a period of evolution of a lot of our cities where they became very fragmented because of some of the burdens that ed describes in his book. we had a flight of the people who created those structures that lifted people. and, but the message in his book is that cities still do that,

10:36 am

but we need to be more conscious of how we do that, how we rebuild that lifting infrastructure. and when you attract young people and people with dreams, when you attract immigrants, as you've pointed out, when you attract entrepreneurs as we're trying to do with the innovation district and all of the other ways we attract entrepreneurs, even the way we try and attract our empty nesters, people who come back with their work and their time and their encore careers and their volunteer time. all of these people's dreams for interesting and better futures create lift, and that creates momentum, and that brings people in to the system. but what actually gives me hope -- your book had one of the saddest sentences i have read in a book in a long time. [laughter] i grew up in cleveland, i actually realized i was pretty old when you said you were born in '67. did you say that? >> yeah, '67.

10:37 am

[laughter] >> well n be 1967 i -- in 1967 i was 12, and my dad would say go to downtown cleveland, it cost a quarter, you could get lunch -- i mean, i feel really old. he was a photojournalist, and he said see the infrastructure of the city. i grew up in a city that was dying where jobs had leavitt, infrastructure had left, community had left. but look at what's going on -- and people were leaving those cities in the midwest. and where were they going? all these young people, this is an amazing thing. he does real research, i do pajama research. i was in my pajamas last night in bed looking up on the ipad about urban studies. so in 1991 we had 30 graduate urban studies programs in the country. now there's 120. young people are not only flocking to cities, they're flocking to the study of cities. and that's going to give us

10:38 am

something very interesting. these are the urban mechanics who are understanding the mechanisms that cities use to lift people. >> let me, let me stop you there and talk about how we keep these people. there are an awful lot of young people in this audience, and i'm so glad you're here this afternoon. public policymakers have been b talking a lot in boston in just the last few years about the cost of living here, talking about how the cost of housing drives people out. and that, you know, that might be true for young and mobile professionals, but it's not what most people talk about. most people, most young people talk about. if you read blogs, blogs written by young people about why they've decided to leave boston after spending their four of plus years here, here's what they say. i've read a lot of these blogs

10:39 am

in the last few years, and they've just almost in a way -- last few days, and they've just kind of stunned me. too small townish, extremely clique key and provincial. the business community is too insular and too close-knit, not enough for entertainment and, ed, not only does the t close early, but the bars close at 2 a.m. >> yeah. [laughter] >> i remember that in my 20s. twenty years ago. >> the first when i read this, i kind of chuckled a little bit. but when i saw these comments repeated by the hundreds and the hundreds and the hundreds, i realized it's not amusing. of we have a cultural problem here in boston what a majority of these young people said was four years plus a couple more, and i'm outta here. not one of them, not one of the comments that i read mentioned the cost of housing except to say, well, you know, you can get a better part in boston for $2,000 a month than you can in new york. if young and the innovative are

10:40 am

the future lifeblood, the present lifeblood and the future, then how do we address this huge cultural and lifestyle gap which is not being greatsed in this -- addressed in this city right now? >> you know, these are such a great set of comments. i think they make one critical central point which is real cities, the real heart of the city, the real essence of a city is not the structures and infrastructure that you see around that are so up pictured in the postcards. it's always the people. it's always about humanity. and no investment in infrastructure makes sense unless it's actually tied to the real needs of the people who are live anything cities. >> that's right. >> the second point i think that's really critical in this is the backdrop to the decline of all these older industrial cities was that transportation costs declined. it was no longer so valuable near the great lakes and coal mines and so forth. and instead of having cities tied down by production advantages, right, like the old general motors factories, cities could grow that were consumer cities, places where people wanted to live. that's one way of understanding

10:41 am

why there's no variable that were the predicts metropolitan area growth than january temperature. above all, meshes went -- americans went towards places that have warmer januaries. now, that is both a challenge and an opportunity because, in fact, we only survive by attracting and retaining talent. and that's not easy. part of it involves getting the basics of city government right. part of it does involve affordable housing, short commutes, low crime rates, livable neighborhoods. but a lot of it is also about fun because the reason why 20-somethings live overwhelmingly in cities is to be near other 20-somethings and to take advantage of fixed-cost things like the boston urban library. now, i'm not going to make any particular comments about our culture here in boston, but it is true that if there are regulations that make it definitely to innovate, if there are barriers erected by various social groups that make it

10:42 am

difficult for smart people to come up with new ideas, that means cities lose their edge. it loses the fact that urban entrepreneurship and competition is just as good for making bars and clubs as it is for making cities productive. half of it is about obtaining the talent and then setting them free. i'm so glad the mayor has joined the food truck fight, because it's one of my favorite crusades. i am deeply passionate about freeing the food truck. [laughter] because the food truck fed me when i was outside of my office building. but i was on a call about 18 months ago with a poor woman who wanted to open her food truck in detroit, and she had been on a one-year regulatory battle to get her food truck through. now, the idea that detroit is saying no to any entrepreneur that quantities to come into detroit -- [laughter] i understand you need some health regs, but basically it's not -- the ombudsman for the or city of detroit on the call, on the public radio call-in, and he

10:43 am

said, well, listen, lady, just start your food truck. we'll never catch you. [laughter] >> barbara berke, weigh in here. >> as you say, you're reading in on blogs, i am getting that message. i have a 22-year-old daughter, stella, just graduated from college, debated, could have picked any city, definitely wanted to live in a city, and i've been hearing train stop early, cabs are too expensive, the bars close early. i get it at my kitchen table. yet you have to explain something, boston has the highest proportion of young adults among the nation's biggest cities. 35% of the people who live in our city are 20-34 years old. i mean, that's if facts. so we may have a very vocal population who are used to texting each other about how thety could be better, but not as many of them are going and

10:44 am

leaving as you might think, and many more of them -- imagine what a magnet we are with all of the schools. i think one of the biggest questions is we could be a much better city for longer night life and later hours and mixing people in a social environment in different places. but we could also be a lot better at introducing all these cities who flock to our downtown and to our universities to our neighborhoods which are really phenomenal and rich and have lots going on. and, you know, so we're being successful, we could be a lot better. >> well, i think i can speak to this personally. i originally hail from chicago, illinois. i'm sure that will come as no surprise to people here, because i'm on trend with all the other black progressive polls. [laughter] who run for office and make history. [applause] [laughter] but i, so i came here to attend

10:45 am

boston university and made a commitment to not only contribute to my campus community, but to connect to the larger city. in fact, that was why i had, well, i'll be honest, it was a good financial package too, and harvard rejected me. [laughter] and believe me, every time i lecture there, i remind them, and i say -- [laughter] ain't this a full circle moment. [laughter] i don't say ain't. in hiway -- that was for effect. but the point is, i originally hail from chicago, illinois, i came here, was a student leader and very active in my campus community, made a commitment to invest in the city as well which was really the turning point in my life and set me on a completely different trajectory. i was president of my student body, i interned for congressman joseph p. kennedy who has since required, a congressman -- retired. i then went on to work for

10:46 am

united states senator john kerry for 11 years and ultimately was recruited to run for office, was elected in 2009. i am 38. this is where you say i look much younger than that. [laughter] i love coming to this space, good lighting. [laughter] but i think, again, i can speak to this personally because now that i am an elected official, the only woman serving on that body and the first woman of color in that body in its history -- mass. [applause] now, why does that matter, why is that relevant? i appreciate the applause, it has nothing to do with a personal achievement. i think it's a shared victory for all of us. it means that the solutions we're developing in government are more comprehensive and fully informed because of that perspective. so i've thought a great deal about this issue of attraction and retex, but more than that, how do we keep native bostonians? because we were losing young people who had been, who were

10:47 am

raised here who were going someplace else. they do come back, though, i have to say that. they sort of go on this pill grammage to see what is out there, but they do come back. and so to ed's point and barbara's as well around social issues, this is an issue i'm working on. again, we have 22 distinctive neighborhoods, and it's very easy for us to be very siloed. and i think what young professionals are looking for and found when i went outside my campus community is community is human connection. and i think, um, restaurants are revolutionary in this way. in my home neighborhood of door chester, i've seen a restaurant like ash month grill transform a blighted corner and turn an entire neighborhood and incentivize other wizs. so restaurants are not only incredible economic anchors because today hire locally, but i think they foster community.

10:48 am

the grill is one of the most diverse venues you could ever patronize in the city. people are looking for community. on the development side, i'm a big believer in smart growth development. i don't own a car. so i want development that is -- [applause] you're applauding. my knees in these stilettos, i don't like that. [laughter] i love the boston brick. [laughter] but, you know, i do take the t to work every morn, i'm in a smart dwroapt developed by trinity financial right in the adams, st. marks area of dorchester. it's mixed use, mixed income as well, and we have an incredible community there. but back to the issue of restaurants before i turn it over to the next question, um, i'm working on the issue of liquor licenses. and i have to say that one of the reasons why, um, our student population and our residents are in conflict is because the second someone starts talking about greater access to liquor

10:49 am

licenses, people think you want to convert main street into new orleans' bourbon street and that you want more bars. what i want are more social venues and an equity in that opportunity, someplace that people can go and raise a glass and, you know, celebrate a christening or a graduation. and the reality is that right now we're seeing an inequity in access to those opportunities. so a neighborhood like the north end has a density of 91 liquor licenses and a depressed neighborhood or neighborhood that could be even more successful like a rocks burg or hyde park is having difficulty procuring those licenses. and restaurants make about 70% of their revenue on their bar. so i think restaurants can play a revolutionary role in building community and in building culture in keeping young professionals here. >> let's stay on real estate development if we can, but let's go bigger, bigger than bricks and mortar, let's talk about steel girders and glass. here's the premise that ed

10:50 am

raises in the book. shiny new real estate, meaning big new developments, may dress up a city, but it doesn't solve its underlying problems. too many city officials think they can bring cities back with some sort of massive reconstruction project. let's stay with our city officials, agree or disagree with that? >> well, let me, if i can speak for a little bit -- >> yes, please. >> i completely agree with what he's saying. you cannot build your way out of a problem with a lack of competitiveness. but one of the things that i did when i was working with the state, i was part of the romney administration as secretary of economic development was understand that boston is doing tremendously well economically, but if we wanted to turn around, um, the pioneer valley or southeastern massachusetts, we had to turn around the fates of new bedford and fall river and lowell and lawrence. and in order to do that, it

10:51 am

wasn't plopping down a single courthouse. that wasn't going to fix it. >> that's right. >> it wasn't going to be building a new walled convention center that had its back to the city, that the only way you can transform a city is with a strategy that builds on the city's assets, that tightly weaves people together around our educational assets, our human as is sets, our community-based organizations, our old industrial assets and some of the new skills that are spinning off of them. and until you knit those pieces together and confine the new narrative lines that come out of that, you know, that the old, that this is a providence and fall river example, the old jewelry business, those little fine skills of making costume jewelry are fonl skills for medical devices. same little set of talents and molding and work. there are all sorts of talents

10:52 am

hidden that can be built on. when you invest in those, you can grow. a lot of people like to think of economic development as attracting businesses with deals. my view is it's come for money, go for money. they never attach, they never stay. we've seen many bad investments. but when you line up a new job producer with a community college and a research investment in the local university and you begin to find the scholarships and the co-ops and the whole ladder that lifts that sector of the economy, that's the way you move from one place to another. and, i mean, i'm really proud about what this state is doing. we have lots of people figuring out how to do this. b math inc. has just launched the gateway cities work. we have all the work at northeastern on the rebirth of older industrial cities. we have this terrific book that ed has written that is beginning to show us the ladders.

10:53 am

he's doing something else really interesting, we have the rappaport scholars. we are in all of our universities in boston and in massachusetts are tilting towards our cities. our lending, their research, their insight, their vision, their bright young people towards engaging at the front line and lifting the city. and so we here, i think, are in a particularly interesting place. and especially when we have a mayor like menino who's been, you know, he was faulted for being an urban mechanic, constantly, constantly working on the basic city services, but people forget that it was always about people and that these structures he's building are these ladders of human development. the acceleration agenda, the boston public schools has built attaching at the low end with a new thriving five early childhood strategy and the success boston strategy and wrapping the out of school time

10:54 am

strategy around this acceleration agenda. our friend paul grow began who's not here is wrapping with all the work that he did to help organize the opportunity agenda to wrap our city's biggest funders around those pipelines. and then that urban mechanics, whether you're building that pipeline for a few bostonian -- menino e was the first mayor to build a new bostonian whole service sector, whether you're lining up your entrepreneurship ladder, whether you're building doing the home ownership training, and who remembers the mayor's don't borrow trouble campaign? wees caped a huge amount of -- we escaped a huge amount of foreclosure because we built the home ownership ladders. you know, we are doing it here. and young, talented students, you're sending us more of them, are the new urban mechanics. some of you may be in the audience to today. but that energy, that talented, that brains around energizing

10:55 am

and engineering a community's capability to lift people, that's what we've got going on in this city. that's why this room is full. >> absolutely. >> i ask the development question because i, i feel compelled to ask a news-oriented question, i don't know why. [laughter] >> paul, -- bob, can i say one thing? >> i'll get you to weigh in in a second. the biggest development on the horizon for boston is the possibility of a billion dollar casino complex being built in east boston at the suffolk downs race track if the developers win the eastern massachusetts casino license, one of the three licenses up for grabs from east to west in the state. the new state gaming commission, of course, has to go through its process, but most insiders you talk to think that the east boston plan has the best chance of any to go all the way. and i'm wondering and, ed, let me start with you here, and then i want to go to ayanna because

10:56 am

she has to consider this on the city council. i'm wondering if if this panel thinks that project will prove to be a try um of the city? >> i'm relatively agnostic on casinos. i'm enough of a libertarian not to think that gambling is a great sin, and i think it's not a terrible thing. on the other hand, it's unlikely to be any sort of a wellspring of further innovation or entrepreneurship that's going to come out of the area. i think the critical issue is whether or not it's going to, you know, make sure it covers any cost to the public sector of maintaining it. but i see it as being neither a game changer, nor a great evil -- although, so i just don't, i just don't have a strong view on it one way or the other. >> i'd like to say something different. the greatest infrastructure project we have in our city right now is the work being done to e restructure the school assignment plan. that is not physical infrastructure, it is human infrastructure, and it is really

10:57 am

big. time is now in this city for people -- >> well, i'm, i mean, i wrote my last column on it. i'm happy -- i've got much stronger views on that than i do the casinos. >> yeah. however we solve it, being able to create a stronger education system that serves people -- >> let me ask ayanna about the casino. [laughter] >> you should answer the infrastructure question though. >> yeah. are you giving that to me because you felt i was just clamoring to comment? [laughter] um, well, it's no secret i'm not a big fan of casinos. but, um, they are coming, and, you know, the lens with which i look at these issues is in making sure there's going to be an excellent opportunity for everyone, that the entire city is benefiting not only in the revenue that stands to be generated, but in the jobs to build the site, in the hotels and the restaurants and the

10:58 am

retail. i will share with you -- again, not to vilify or demonize any one industry -- my own personal experiences being raised by a single parent with a father who struggled with drug addiction and was in and out of jail in my life in supporting that addiction, i just personally am very conflicted about things that i see as contributing to the social ills that i work to combat every day. like human trafficking, like drug abuse, like alcohol abuse. speaking about -- >> domestic violence. >> domestic violence. again, i don't want to, you know, demonize or vilify any one industry, but the data does show that there are a confluence of things that contribute to these social ills. so that's what i would say about casinos. two quick points, your point about the schools which ties into the question i wanted to speak to earlier, we talk about a commitment to -- and i know the mayor shares this, as does our superintendent -- to teach

10:59 am

the whole child. but we are not being, we're being disinvenn juice if we don't -- disingenuous if we don't acknowledge most children are not entering that school whole. they are broken, and we have to have a commitment to their social/emotional wellness and that's not just a moral issue. there's such a thing as social/emotional intelligence as well. in one's ability to, um, learn executive function and to ultimately be more competitive and better prepared for the work force. there's such an emphasis on science, technology, engineering and math. i would never give short. >> lift to -- shrift to that, but i would be remiss if i did not say that we need an a in that -- [applause] because without art, there won't be any innovation. [applause] there won't be any innovation. so what we need is theme, and when it comes to our economy as well, i'm a very aggressive

11:00 am

advocate and a believer in the creative economy. and i know our mayor shares a commitment to that in everything from public art to arts education to arts in education. you know, when i travel, people do talk about that school across the river, harvard, but the next school they'll ask me about is berkeley. you know, we boast so many incredible institutions related to the creative economy, and so i can't be here amongst the tribe and not talk about the humanities and arts. ..

11:01 am

>> mining is sam. [applause] >> i'm glad that you touched on education. my question is obviously the headquarters are here in boston but also in other cities in america and two others overseas. our school system for failure and what do you believe is the role of the community of the city of the federal government and so on? because it seems the urban school was struggling. chicago, l.a., atlanta, so long. >> of course it's not a boston thing. overall boston public schools are doing quite well to the

11:02 am

other urban counterparts. but that is a statement that is laced with a sense of tragedy and triumph. it is -- i can't possibly think that the failure of urban public-school says permanent. i can't wake up that way. i can't imagine that that is what we are going to do to our city children forever. i believe that we are making improvements and the test score data does show that and we will continue to make improvements. part of the challenge of the start fighting is the cities have an abundance of people with less needs. not because the city's make people poor but because they attract the poor with a promise of economic opportunity, better social service and the ability to get around without buying a car for every adult. some of my work looks at what happens of poverty near the subway stops when you build a subway poverty that doesn't mean the subways are hurting the

11:03 am

people nearby it means they are providing a means for people with less means to actually get around. but the cities are going to attract people with less means. it's going to make it more difficult to provide an urban education because parents with assets and parents with an abundance of capital can provide things for the kids to supplement what goes on in the schools. this makes this an enormous challenge. now i think this involves many different strategies being tried in different ways. unquestionably had been the federal government has a role in this. it has a role in this because education is the best means we know of for tough finding the equality and justice in the world. there is no census for distribution among the adult but i believe this country is not so far gone that we cannot get national consensus beyond the needs of every american. should have the opportunity for an education to afford. and we need the federal government involved because when we try to do redistribution of the local level and a meeting

11:04 am

involving the poor people, it doesn't work. we have tried this in the 50's, 60's and 70's. the company's just leave if you try to run a local welfare state. you need the federal dollars to do this and often pushing against. one of the great advantages is that it pushed up the charter school limit within this community. now, i think in terms of actual strategies -- i certainly agree with ayanna. my father was a curator at the museum of art if you can believe up to enrich and empower all of our lives. but there's a lot to be said for the work of george guttman shows each year and math education for an african-american between 80 to 90 is the result of the nation of this report increased adult earnings by 8%. a big payoff to actually have in the quantitative skills. the other thing we know is that many charter schools have been successful and we have the lottery results in boston that have shown. i'm enough of an economist to

11:05 am

believe in innovation and the charter schools to make that happen. that being said, we cannot forget on the public school system as a whole cannot let that go into the most critical ingredient that we know in school these teachers. it's all about the human capital. it's about the teacher level. to meet public school teachers are heroes. they do every day fighting often difficult conditions to make their lives better for people who are starting with less. the work of my colleague looks at the impact of teachers on test scores and compares it with an impact of the same teachers earnings as adults. even though the impact of teachers on test scores comes out every year, the impact on teachers does not. and experience does not lie. some teachers early in our lives that change does and open to us to something along the way is exactly what cities do, right? it's about this process of learning for people who were close to you. and so there's nothing that's more critical in terms of rebuilding and enlarging our urban school systems.

11:06 am

they have plenty of support from federal government in terms of resources and the right incentives and the freedom to get the best possible teachers that they can have and the ability to pay them well. and i am enough of ab leader they should face competition from charter schools as long as the charter schools are properly regulated. >> i agree with all of that. i would also add it is the symbiotic partnership of many things. the confluence of things. i think that engagement is incredibly important. and so, for ultimately if we are not working on the social determinants and the nonacademic barriers that complicate and put in conflict that the child's ability to succeed is classically and also in life, then this is all for naught. so i do believe all of the issues that we have been discussing are critical components of that because you can have a good school but if there is a depressed community

11:07 am

behind it and families that are destabilized because they are working two jobs or they don't have access to adult basic education, how can they advocate for their child and navigate a school system for them? so it has to be a holistic response. >> i want to make an additional point that i think is an interesting one. a lot of people say because we have so many immigrants and mauney slash speakers that it's making it harder for our schools to teach and succeed. fighting que me know that about 45% of the public-school children do not speak english at home. what you might not know is some of the terrific resources about how english-language lerner children are doing in boston. and when you disaggregate them by the ones that have almost no english, they are not doing so well. when you see the children that have gone through the system and have a little bit of language, they are doing equally well.

11:08 am

when you look at the kids that have been through the system and who are former english-language learners, they are outperforming the native born children in the boston public schools and we need to look at the valedictorian. we are graduating from on all kids who are doing a multilingual coming and we need the opportunity and the structures that left these kids up. and i think the reason that they are so native-born children come if you think that terry carefully, these native-born children, their parents were field by schools, and in some cases their grandparents were filled by the failure of urban public schools, and these parents do not believe in their personal experience that schools deliver opportunity. and so, until we can reach back to serve the whole family, not just of the whole child so we

11:09 am

can reach back into early childhood, can we reach back to support parents think like we are -- reach back with. university and the investments in the city. reach back with adult education. when we reach back we are going to move forward when we get multiple generations, and that is what the city is doing now because we are performing, but we have a huge way to go. >> we are just about out of time. by the way over here on your left, go ahead, sir. >> mother and father from hyde park. [applause] >> i lived in beacon hill. i find that in addition to its size which is three manageable, one of the keys to success of boston is a high regard that the city government has for government, and in the era when

11:10 am

the civic engagement and government at all levels is held in esteem, and erroneously in my view, boston stands apart and is quite successful because of that intimate involvement. no one has been to a christening in boston in the last ten years that many may not have been too. [laughter] the counselor etc. so those of you from outside of the city government officials, city officials, do you share that view? >> absolutely i share that view. i have enormous respect for both the city council and the administration and i think that you are absolutely right the cities need government respecting government. one way to think about this is an abundance of land but when people are crowded together the

11:11 am

need management to deal with congestion and contagious diseases and urban schools and all of the issues we are facing. those problems don't get solved by the private sector. they actually need a functioning government. so it's always been. it's why 100 years ago we have said he governments have long before we had an active government because it is so critical that we actually deal with the problems of boston has and that is a result of its density but there's a reason why people in boston like people more than in montana. they needed more. and that is central and it isn't going away and we are a absolutely blessed in this regard. we continue to have problems like the school system that continue to need more work. but we get nowhere by vilifying government as a whole and indeed we should cherish our leaders as well as occasionally to do better on things as a part of the space process. but we should fundamentally be grateful for them and thank them for the sacrifices they make. let's save our vilification for those people that start at the

11:12 am

national level. [applause] >> along those lines, let me ask one more question. we are 15 days away, as of today, from what has been widely called the most important presidential election of our lifetime given that choice between the two men running for office is very, very different. as we are in the final days, let me ask you this question, d.c. greater challenges facing cities, boston in particular under the mitt romney presidency as opposed to the continued brought about -- barack obama. >> the track record of the cities is very, very weak and that is true under both parties. very well meaning that we can occasionally not well-meaning but i think that is the larger challenge. not one candidate versus the other but how to create an agenda that makes sense. one that doesn't come and again,

11:13 am

this means pushing bad on policies that need massive spending on highways for the general tax revenues. she's the most urban president we have had since teddy roosevelt and yet we have the infrastructure stimulus package and then the latest highway bill. we had a massive infusion of general tax revenues to pay for drivers. i have no idea why we are driving people to drive long distances. i am a person that believes interest the people should be free to try it if they pay for the cost of their action but we shouldn't be driving the students. we shouldn't be engaging in social engineering that uses federal tax policy to massively subsidize people to move into the to move out of urban apartments to buy homes, which subsidizes to bet on to the housing market which also bribes them to build larger homes. i am a homeowner myself but i think having a current, mortgage interest deduction is crazy. we should slowly on hundred

11:14 am

thousand dollars a year and most of all, we need to have even more commitment to the urban schools to it but i would like a world in which we did was subsidizing and have the fed have less engagement and leave cities if they are in power and have the resources to solve their own problems. i would much rather have that happening. some things to remember race to the top started with obama. we are doing things at the national level to reduce the education disparity. obamacare started with romney and was romney care before and that giving everyone access to health insurance is again one of the most important things we can do in this nation to a level the disparities of health and the disparity created by the lack of access to the health insurance. so, we have bipartisan support t

107 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

CSPAN2 Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11